This section includes:

- Gender Dysphoria and Autism Correlation – Explores a strong link between autism and gender dysphoria.

- Childhood Trauma and Gender Identity – Research suggests a high prevalence of childhood trauma, including sexual abuse, among individuals with gender dysphoria.

- Mental Health Comorbidities – Trans-identifying individuals have significantly higher rates of anxiety, depression, ADHD, and other psychological conditions.

- Biology vs. Ideology – Explores the legitimacy of some brain studies suggesting structural differences in transgender individuals, where critics argue that gender identity is shaped more by social and psychological influences

- Ethical Concerns in Therapy – The debate over affirmation therapy vs. reality-based therapy highlights concerns about whether immediate affirmation is the best approach, especially given high rates of desistance among gender-dysphoric youth if left untreated.

- Medicalization and Minors – Questions the use (and necessity) of puberty blockers, hormones, and surgeries for minors, with growing international pushback and restrictions of pediatric medical transitions due to the lack of long-term safety data.

- Philosophical and Social Ramifications – The legal and cultural enforcement of gender identity over biological sex raises concerns about free speech, women’s rights, and medical ethics.

- Balancing Science and Compassion – A sustainable approach requires acknowledging biological realities while ensuring gender-dysphoric individuals receive ethical and evidence-based care, free from ideological pressure.

Introduction:

Gender dysphoria – the distress arising from a mismatch between one’s experienced gender and birth sex – lies at the intersection of science, psychology, and ideology. It raises complex questions: What factors correlate with identifying as transgender? Is gender identity “hard-wired” in the brain or shaped by culture? How should therapists balance affirming a patient’s identity with objective reality? And what are the broader implications when personal identity is treated as a medically and legally enforceable fact? This analysis delves into each of these areas, drawing on empirical data, case studies, and expert commentary to provide a comprehensive understanding.

1. Scientific Correlations

Autism Spectrum Overlap with Gender Dysphoria

A striking body of research has uncovered elevated rates of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) among transgender-identifying individuals. In the largest study to date (over 640,000 participants), transgender and gender-diverse people were three to six times more likely to be autistic than cisgender people ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ) ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ). About 24% of transgender/gender-diverse respondents were autistic, compared to 5% of cisgender participants (Study finds higher rates of gender diversity among autistic individuals | Autism Speaks) (Study finds higher rates of gender diversity among autistic individuals | Autism Speaks) – a nearly quadruple to quintuple prevalence. This overlap appears bidirectional: autistic people are also more likely to identify as gender-diverse than neurotypical peers ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ).

Several potential explanations have been proposed for this correlation. One idea is that certain autistic traits – such as sensory sensitivities, atypical social cognition, intense focus on specific interests, and lower empathy – might predispose individuals to question gender norms or feel discomfort with their bodies ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ). For example, sensory issues could make the physical changes of puberty especially distressing, or a cognitively rigid focus on “being one of the boys/girls” might lead an autistic youth to identify intensely with the opposite sex. Another hypothesis is that autistic individuals are less swayed by social conventions, so they may express gender variance more freely. Neurologically, the “extreme male brain” theory (which posits that autism involves cognitive patterns more common in males) has been floated to explain why autistic traits and gender variance co-occur, especially in birth-assigned females. Ultimately, researchers note the overlap is real, but caution against assuming causation – autism does not necessarily cause gender dysphoria, nor vice versa (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria). Instead, clinicians are urged to support autistic transgender people holistically: being both autistic and gender-diverse can compound minority stress and mental health struggles ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ) ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ). Notably, one study found nearly 70% of autistic youth with gender dysphoria desired medical transition care, underscoring the need for sensitive, case-by-case treatment rather than blanket skepticism ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ).

Childhood Trauma and Gender Dysphoria

Another correlation explored in the literature is the link between childhood adversity or sexual trauma and later gender dysphoria. Multiple studies have found high rates of early abuse among gender-dysphoric and transgender individuals. For instance, one clinical sample reported that over half (55%) of transsexual participants had experienced unwanted sexual contact before age 18 (Prevalence of Childhood Trauma in a Clinical Population of Transsexual People | CoLab). Similarly, a 2021 analysis noted “increased rates of sexual abuse (>50%) in individuals with GD (Gender Dysphoria)” ( Gender dysphoria: prejudice from childhood to adulthood, but no impact on inflammation. A cross-sectional controlled study – PMC ). Beyond sexual abuse, gender-dysphoric adults also report elevated levels of physical abuse, emotional neglect, and other forms of childhood trauma. In one study of 95 adults with gender dysphoria, a staggering 56% had suffered four or more types of early traumatic experiences, a much higher poly-victimization rate than in control populations (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria). These adversities often coincided with disrupted attachment patterns – e.g. dysfunctional family dynamics or absent parents – hinting that unstable early environments might play a role in some cases (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria) (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria).

What might explain this link? Some psychologists theorize that gender dysphoria can sometimes emerge as a coping mechanism or dissociative response to trauma. Classic case reports described children who, after abuse or loss, began identifying as another gender as a way to “escape” their reality or identity. Coates and Person (1985), for example, hypothesized that in certain cases a young child might unconsciously adopt an opposite-gender persona as an “extreme dissociative defense” against early relational trauma (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria). In plainer terms, a child who was sexually abused might fantasize “If I were a boy (or girl), this wouldn’t have happened to me,” and that fantasy solidifies into a dysphoric identity. There are also accounts of individuals who report transitioning to flee or erase a source of pain – e.g. a boy bullied or abused for being “effeminate” who later lives as female to feel safer, or a girl who was sexually assaulted and then identifies as male to avoid sexualization. Detransitioned author Walt Heyer has noted anecdotally that “Childhood sexual abuse is an experience common to many… who write me with regret about changing genders”, suggesting unaddressed trauma can fuel a transient transgender identity (Childhood Sexual Abuse, Gender Dysphoria, and Transition Regret: Billy’s Story – Public Discourse). However, it’s critical to emphasize that these are case-based hypotheses; as a 2018 review concluded, “to date, no solid empirical support” confirms that childhood trauma directly causes gender dysphoria in a generalized way (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria). Instead, trauma is best seen as one of many factors that might co-occur with gender dysphoria. Indeed, the high prevalence of adverse experiences is concerning in its own right: childhood maltreatment in trans populations is linked to worse mental health, higher suicide risk, and even greater body dissatisfaction later on ( Gender dysphoria: prejudice from childhood to adulthood, but no impact on inflammation. A cross-sectional controlled study – PMC ) ( Gender dysphoria: prejudice from childhood to adulthood, but no impact on inflammation. A cross-sectional controlled study – PMC ). Whether or not trauma triggers dysphoria, those who have endured it clearly need compassionate psychological care alongside any gender-related interventions.

Mental Health Comorbidities and Psychological Factors

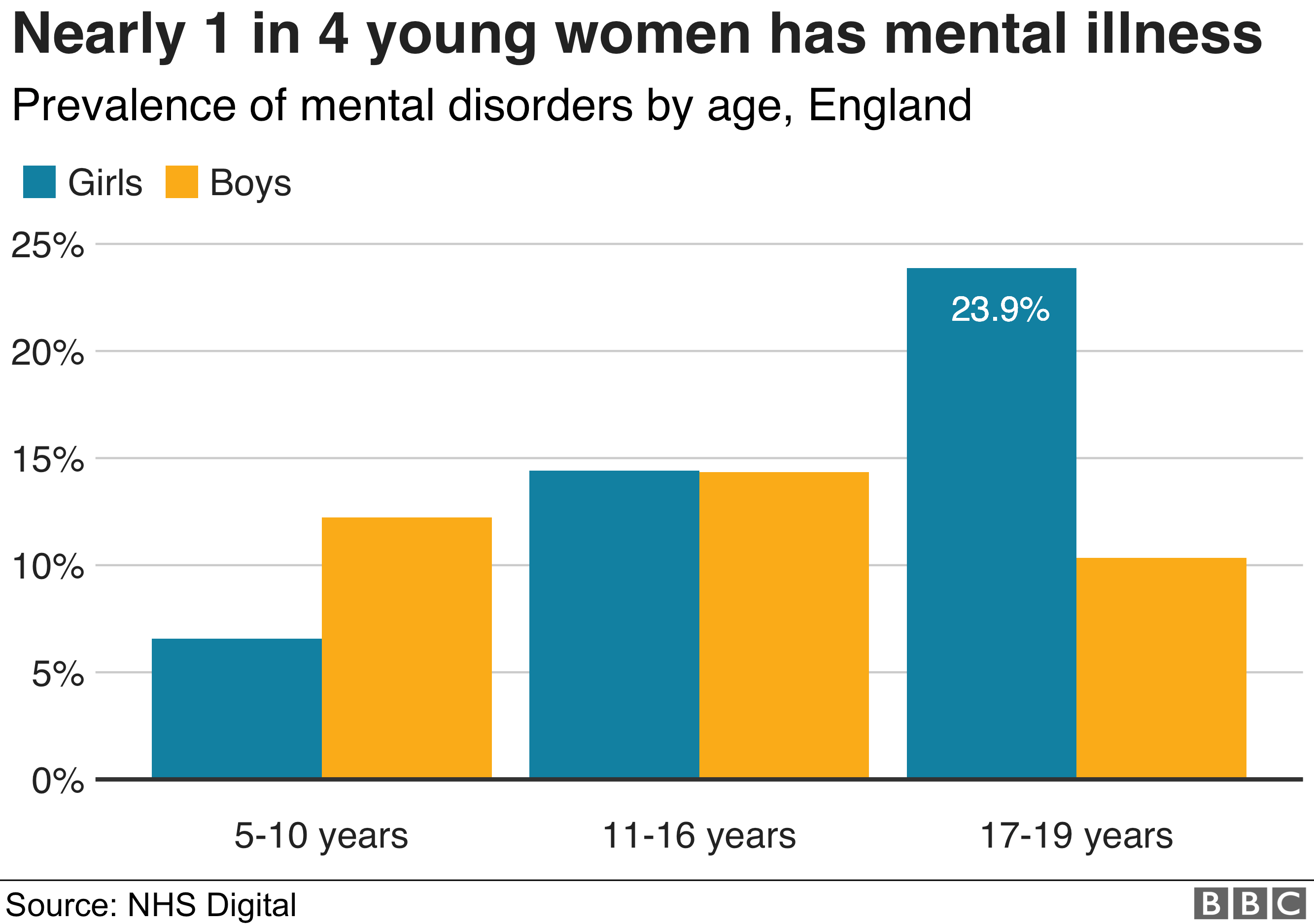

Gender dysphoria does not exist in a vacuum; it often intersects with other mental health conditions and psychological vulnerabilities. Research consistently finds that transgender individuals, especially youth, have higher rates of mood disorders, anxiety, self-harm, and neurodevelopmental conditions than the general population ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ) ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ). One campus survey in the U.S. found that gender-minority young adults had 4.3 times higher odds of having at least one mental health problem compared to their cisgender peers (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). Likewise, a systematic review reported that 53.2% of people diagnosed with gender dysphoria had a history of at least one other mental disorder in their lifetime (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). These disorders range from depression and anxiety to PTSD, eating disorders, substance abuse, and personality disorders. For example, among gender-dysphoric adolescents in one clinic, 21% had an anxiety disorder, 12% a mood disorder, and 11% a disruptive behavioral disorder – rates markedly above population norms. Autism and ADHD are also overrepresented, as discussed; one study found 15% of trans youth had ADHD (similar to the autism rates) (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender), and children with ADHD were 6.6 times more likely to express gender variance than non-ADHD peers (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). Taken together, these findings portray a landscape where co-occurring psychological issues are common rather than exception.

It’s important to ask: are these mental health challenges contributing factors, consequences, or merely coincidences? In many cases, it may be a bit of each. Gender dysphoria can certainly cause distress that leads to depression or suicidal ideation (the emotional toll of feeling “in the wrong body” or facing social stigma is heavy). There’s also the minority stress model – the chronic stress of being transgender in an often-hostile society can fuel anxiety, trauma, and self-harm over time ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ). On the flip side, pre-existing mental conditions might make a person more vulnerable to developing gender dysphoria or adopting a transgender identity, especially in today’s climate. For instance, Lisa Littman’s survey of parents of youth with so-called rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) found 62.5% of these youths had at least one mental or neurodevelopmental issue prior to their gender identity change (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). Many struggled with processing emotions and had a history of trauma or social difficulty, suggesting their dysphoria “came out of the blue” in a context of other turmoil (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). Clinicians like Dr. Kenneth Zucker have long observed that a “large percentage of adolescents referred for gender dysphoria have a substantial co-occurring history of psychosocial and psychological vulnerability” (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). In practice, this could mean a teen girl with undiagnosed autism and depression suddenly believes transitioning to male will fix her unhappiness, or a young person with a history of abuse adopts a trans identity hoping to reinvent themselves. The cause-effect relationship is often tangled. What is clear is that comprehensive assessment is vital – underlying issues (such as trauma, autism, bipolar disorder, or borderline personality traits) should be addressed in tandem with gender feelings, not ignored. Even after medical transition, mental health disparities persist. A long-term Swedish follow-up famously found that post-surgery transsexual individuals had higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization and suicide attempts than the general population, indicating transition wasn’t a cure-all for their deeper psychological needs (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender). All of this underscores that gender dysphoria typically exists as part of a complex psychological picture, not as a simple isolated condition. Effective care must recognize and treat the whole person, not just the gender dysphoria in isolation.

2. Biology vs. Ideology

Innate Identity or Social Construct?

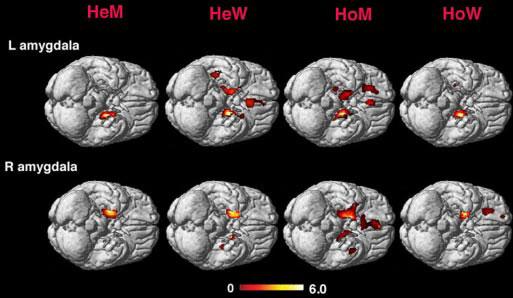

A central tension in the transgender debate is whether gender identity is a biologically innate trait – something essentially hard-wired in the brain – or a socially constructed identity influenced by culture and personal experience. The mainstream narrative in recent years often asserts that “trans people are born that way”, with a gender identity that is fundamentally innate (and sometimes at odds with their anatomy). Indeed, some scientific studies lend credence to an innate component. Brain imaging research has identified subtle neuroanatomical differences in transgender individuals that distinguish them from cisgender controls. For example, a 2022 MRI study of trans women (biological males who identify as female, scanned before any hormone therapy) found their brain structural profile fell in-between that of cisgender males and females – significantly shifted toward the female side, though not identical ( Brain Sex in Transgender Women Is Shifted towards Gender Identity – PMC ). The authors concluded that transgender brains appeared “shifted away from their biological sex towards their gender identity” ( Brain Sex in Transgender Women Is Shifted towards Gender Identity – PMC ). Similarly, earlier studies of specific brain regions (like the BSTc and insula) reported patterns more typical of the experienced gender in trans people. These findings are often cited to argue that transgender identity has a biological basis – possibly rooted in genetic factors or prenatal hormone exposures that influence brain development ( Brain Sex in Transgender Women Is Shifted towards Gender Identity – PMC ). In other words, a transgender woman might literally have a brain that is structurally closer to what we’d expect in a female, which could make her feel female. However, these brain studies are not without limitations: sample sizes are small, differences are averages (there’s overlap), and it’s hard to untangle cause and effect. Are trans brains different because of an innate identity, or do years of identifying/behaving as another gender (and associated experiences or even hormone use) shape the brain? Moreover, many of these studies have failed to control for sexual orientation, which may be a significant confounding variable. Research on gay men and lesbians has already shown that their brain structures and responses sometimes resemble those of the opposite sex – for example, gay men’s brain hemispheres tend to show similarities with straight women, and lesbians with straight men ( Brain structure changes associated with sexual orientation ). Soh and others have noted that the brain features cited in support of a transgender brain type may, in many cases, reflect same-sex attraction rather than gender identity itself. Given that many transgender individuals are also homosexual, these patterns could be better understood as evidence of sexual orientation, not proof of an innate gender mismatch. This raises important questions about how such findings are interpreted—and whether they are being used to support ideological claims that exceed what the data can actually confirm.

On the flip side, a growing chorus of experts and commentators suggest that social and psychological factors play a dominant role in shaping gender identity – especially given the rapid changes in who is identifying as trans. Citing dramatic epidemiological shifts, they argue gender dysphoria can sometimes behave more like a social contagion or cultural phenomenon than a fixed inborn trait. Consider that until roughly 10 years ago, the typical trans patient was either an adult male with longstanding cross-gender feelings or a very young effeminate boy – cases that often began in early childhood. Yet in the last decade, clinics have seen an explosion of adolescents (especially teen girls) suddenly identifying as transgender with no childhood history. In the U.K., the Tavistock gender clinic reported a 4,400% rise in teen female referrals over the previous decade (). The graph below illustrates this surge: referrals to the UK youth gender service skyrocketed from only dozens per year in the early 2000s to over 2,700 in 2019-2020, with adolescent girls comprising the majority of cases.

(Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service Data – Gender Identity Research & Education Society) Annual number of children and adolescents referred to the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service in the UK, 2003–2020. An exponential rise – especially among birth-registered females (yellow) – is evident beginning around 2015 (Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service Data – Gender Identity Research & Education Society).

Such an exponential increase cannot be explained by genetics (genes don’t change that fast) or even prenatal factors; it strongly suggests cultural influences and changing social norms. Dr. Lisa Littman’s 2018 study coined the term “Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria” (ROGD) to describe this phenomenon, hypothesizing that peer influence and Internet/social media content are significant drivers (). Indeed, parents reported that many of these teens “experienced this atypical gender dysphoria out of the blue,” often after bingeing on YouTube transition videos or amid a friend group where multiple girls suddenly identified as trans (). Journalist Abigail Shrier, who investigated the trend in her book Irreversible Damage, was struck by how unlike classic transsexualism this new cohort seemed. These were often socially awkward, anxious young women who previously identified as lesbian or simply struggled with puberty, now binding their breasts and demanding testosterone after immersing in online transgender forums. Shrier’s research and interviews led her to conclude that “this was not the typical presentation of gender dysphoria” at all – rather, it bore the hallmarks of a social craze, with peer contagion and psychosocial maladaptation at its core (). In her Senate testimony, Shrier pointed out that clusters of transgender-identification have formed within friend groups and schools, analogous to past spikes in eating disorders or even collective delusions in troubled teens () (). In short, the argument goes, if gender identity were purely innate and biological, we wouldn’t expect it to suddenly surge 20- or 50-fold in certain demographics. Such surges imply that ideology and social messaging (“if you feel uncomfortable as a girl, maybe you’re really a boy”) are playing a powerful role.

Neuroscientist Debra Soh’s Critique of Gender Ideology

Neuroscientist Dr. Debra Soh is one of the outspoken voices challenging the prevailing orthodoxy on gender. Armed with years of sex research, she argues that much of what we’re told about gender identity today is ideologically driven and not backed by solid science. Soh points out that it has become almost taboo in academic and medical circles to question the new dogmas, resulting in a “cult-like” climate where feelings are privileged over facts. In an interview about her book The End of Gender, Soh remarked that “gender has been transformed into a cult-like idea, and Western society seems willing to give up factual knowledge about sex and gender.” She notes that researchers face pressure to only ask “polite questions” that confirm activists’ beliefs, and that “the political left is starting to suppress science” whenever findings counter the narrative (CNE.news). One example she gives is the issue of childhood-onset dysphoria. Decades of studies (from Zucker, Bradley, Green, etc.) showed that the majority of young children with gender dysphoria – typically ~80% – eventually outgrow those feelings by adolescence if not socially transitioned. Most of these kids ended up identifying as gay or lesbian, not transgender, once puberty hit (CNE.news). This is a well-documented outcome in clinical research. Yet, Soh observes, “all the mainstream media [now] proclaim that early transition for a child should be supported,” with little mention of the science that most dysphoric kids will desist (CNE.news). She finds it “disturbing” that politically driven guidelines encourage immediately affirming a child as trans, when “scientifically speaking, the situation is different” (CNE.news). In her view, ignoring the high desistance rates is a triumph of ideology over evidence – an example of “giving up factual knowledge” because it’s deemed insensitive. Soh also takes aim at the trendy claims that gender is purely a social construct or that there are infinite genders. She labels these ideas “myths” and says she wrote her book to “debunk [them] one by one… with scientific facts.” (CNE.news). For instance, while gender expression has cultural aspects, biological sex differences in the brain and behavior are very real – and by extension, transgender individuals likely exist due to atypical biological development (as opposed to being proof that anyone can be whatever gender they feel like). In short, Debra Soh’s stance is that biology matters and today’s gender discourse has veered into ideological zealotry, to the point of suppressing researchers and clinicians who don’t toe the party line.

Abigail Shrier and the “Social contagion” of Trans Identity

Abigail Shrier, though a journalist by profession, has become a prominent voice highlighting the ideological and social influences affecting gender identity in youth. Her focus has been on the sudden rise of trans-identification among teenage girls, which she believes is “a social contagion, not an innate identity unfolding.” Through interviews with families, clinicians, and detransitioned young women, Shrier documented how peer pressure, online communities, and activist counselors have cultivated an environment where troubled teen girls interpret their angst as being “transgender.” She cites cases of entire friend groups coming out as trans within a short span, adolescents who had never shown childhood dysphoria yet abruptly insisted on hormones after marathon Tumblr sessions, and therapists who immediately affirm without probing other issues (). The ideological underpinnings here include the notion (spread on social media and in some schools) that gender is fluid, identity is paramount, and anyone who questions a teen’s self-diagnosis is a bigot. Shrier argues that these ideas have essentially seduced a vulnerable population – namely adolescent girls often grappling with body image, sexuality, or social belonging. In earlier eras, such girls might have fallen into anorexia, self-harm, or goth subcultures; today, they declare a trans identity as a purported solution to their discomfort. One poignant observation she makes is that many of these girls are same-sex attracted (lesbian) or gender-nonconforming in their interests – and in a less ideologically charged world, they would likely just grow up to be healthy gay women. Instead, the current climate may be pathologizing their personalities, telling them that if they don’t fit female stereotypes or hate their bodies, they must actually be boys. Thus, Shrier and others see a form of “conversion” happening under the banner of gender ideology – ironically converting would-be lesbians into straight trans men via hormones and surgeries. While this perspective is hotly contested by trans activists (who deny that social contagion plays any role and view such claims as delegitimizing trans people), it has gained traction as multiple countries report spikes in adolescent gender dysphoria. Supporting Shrier’s alarm, clinicians at the UK Tavistock clinic wrote in 2018 about the need to consider social influence on these late-presenting cases, and a former head of that clinic expressed concern that many teens were “simply caught up in something.” Even Dr. Kenneth Zucker, a veteran in this field, has acknowledged that the sociocultural context in recent years is contributing to more teens declaring trans identities (). In summary, Shrier’s work shines light on the ideological roots of the current transgender youth surge: an environment that normalizes and even glamorizes transitioning, potentially at the expense of treating underlying mental health issues.

Historical Shifts in Classification and Treatment

The understanding and classification of gender dysphoria have evolved markedly over time – a story that itself reflects the push-pull of scientific knowledge and changing social attitudes. In earlier diagnostic manuals (DSM-III and DSM-IV), the condition was termed “Gender Identity Disorder” (GID) and explicitly treated as a psychiatric disorder in which one’s gender identity was at odds with biological sex. The emphasis was on the identity conflict itself as pathological. However, with the publication of DSM-5 in 2013, the diagnosis was renamed “Gender Dysphoria” – a deliberate move to depathologize gender variance while still recognizing the intense distress that can accompany it (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia). As the APA explained, “diverse gender identities are not in themselves disordered, and disorder solely relates to distress.” In other words, it’s not “being trans” that’s a mental illness, but the dysphoria (distress) that may come with it (What Is Gender Dysphoria? A Critical Systematic Narrative Review). This change was driven in part by advocacy to reduce stigma: labeling someone as having a “disorder” simply for being transgender was seen as unnecessarily pathologizing. The subtyping by sexual orientation was also removed (previously clinicians noted whether a patient was attracted to males, females, both, or neither – reflecting an older theory that there are different types of transsexualism). Now, the focus is just on alleviating dysphoric distress. Similarly, the World Health Organization’s latest ICD-11 in 2019 reclassified “Gender Incongruence” out of the mental disorders chapter, moving it to a sexual health category (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia). These shifts signify a broader historic reframing of gender dysphoria from a psychiatric abnormality to a medical condition or even simply a human variation.

Accompanying the nosological changes have been treatment philosophy changes. Historically (mid-20th century), someone with gender identity conflict might have been subjected to talk therapy aimed at alignment with birth sex (or even aversive therapies to discourage cross-gender feelings). By the late 20th century, however, a “gender-affirmative” approach emerged in specialized gender clinics, where the goal was to help a patient transition socially and physically to relieve dysphoria. Harry Benjamin’s work in the 1960s set the stage for providing hormones and surgeries to transsexuals under strict criteria – typically only adults who had a persistent cross-gender identification and had undergone extensive evaluation. The Standards of Care developed by WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health) initially required things like living full-time in the desired gender for a year (the “real-life test”) and letters from mental health professionals before medical intervention (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia). Those gatekeeping standards have gradually loosened in many places, moving towards an informed-consent model for adults. In children, the Dutch protocol introduced in the 2000s pioneered puberty blockers to buy time, followed by hormones at 16 and surgery at 18 for those with early-onset dysphoria. This protocol was predicated on careful psychological vetting and the idea that only a small, insistent group would be candidates.

In the 2010s, however, activist pressure and ideological currents pushed the field further towards immediate affirmation. Many mental health practitioners were taught that any attempt to explore or question a transgender client’s self-declared identity was “conversion therapy”. Consequently, the role of psychotherapy shifted in many clinics from probing “why do you feel this way?” to simply facilitating transition. Some clinicians raised concerns that other mental issues were being overlooked in this rush. For example, an internal review at the Tavistock clinic found staff felt unable to challenge young patients for fear of being seen as unsupportive, even when complex trauma or autism was present. Over the last few years, there’s been something of a reassessment in parts of the world. Sweden and Finland, after years of relatively permissive practice, have pulled back on pediatric medical transitions (we’ll detail this in the next section) in light of weak evidence for long-term benefit. The UK’s NHS ordered an independent review (the Cass Review) which in 2022 recommended shutting down Tavistock GIDS in favor of regional centers with more holistic care, emphasizing mental health and calling for research because existing evidence for puberty blocker outcomes was very uncertain (The real story on Europe’s transgender debate – POLITICO) (The real story on Europe’s transgender debate – POLITICO). These developments show how the pendulum can swing: classifications changed to be less stigmatizing and treatments became more affirming in response to social justice concerns – “to reduce the stigma and prejudice experienced by persons with GD” ( Gender dysphoria: prejudice from childhood to adulthood, but no impact on inflammation. A cross-sectional controlled study – PMC ) – yet now some experts worry that perhaps too much ideology (and too little evidence) influenced those practices. History is essentially being rewritten in real-time, as medicine tries to find an ethical course between acknowledging transgender identities and avoiding harm from premature, ideologically driven interventions.

3. Ethical Concerns in Therapy

Affirmation vs. “Reality-Based” Therapy Approaches

One of the most heated debates in clinical circles is over the appropriate therapeutic approach to gender dysphoria: Gender-affirming therapy versus what some call “reality-based” or exploratory therapy. In a gender-affirming model, the therapist takes the patient’s stated gender identity at face value and supports them in that identity, helping them socially transition and access medical treatments as needed. In contrast, a “reality-based” (or exploratory) approach maintains a degree of clinical skepticism, exploring possible underlying causes for the dysphoria and gently challenging false beliefs – much as a therapist would with any other identity-related conflict or dysmorphic feeling. To its critics, affirmation can look like immediately “rubber-stamping” a patient’s self-diagnosis (for instance, telling a troubled teen, “yes, you’re really a boy” after a single session), whereas reality-focused therapy can look to its critics like denying the patient’s lived reality and causing harm by not affirming.

Proponents of gender-affirming therapy argue that it is cruel and unethical to tell someone their deeply felt identity is not real. They point to high suicide attempt rates among transgender people and suggest that affirming therapy literally saves lives by reducing rejection and self-hatred. Indeed, many major medical organizations have issued statements opposing any therapy that tries to change a person’s gender identity (labeling that as a form of discredited “conversion therapy”) (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia). The American Psychological Association, for example, advises that affirming a child’s gender exploration is best for mental health, as opposed to pressuring them to conform to their birth sex. Affirmation, in this context, is seen as acceptance and support – analogous to how one would support a gay youth in coming out, rather than trying to make them straight. Importantly, an affirming therapist can still offer psychological help (addressing depression, anxiety, etc.), but they will not directly challenge the core belief of being another gender.

On the other hand, proponents of a more exploratory or reality-oriented therapy raise the question: when is affirmation appropriate and when might it be reinforcing a delusion or misunderstanding? In virtually every other area of mental health, therapists do not automatically affirm a patient’s subjective beliefs about themselves. If a patient with schizophrenia says, “I am King Arthur,” the therapist does not nod and say “Yes your majesty.” If a teenage girl with anorexia insists “I’m fat” when she’s dangerously underweight, we don’t celebrate her insight – we recognize that as a false belief central to her disorder and work to change it. Many clinicians have drawn an analogy between gender dysphoria and other dysmorphias or identity delusions: the person has a fixed belief (“I’m really a man,” or “this limb doesn’t belong to me,” or “I’m hideously ugly”) that conflicts with physical reality. In such cases, the usual therapeutic approach is to use gentle reality-testing and treatment of the mind, rather than to alter the body to fit the belief. A patient with Body Integrity Identity Disorder (who might earnestly want a healthy limb amputated to satisfy an identity as an amputee) is generally not offered surgery but rather psychological care; an anorexic is not given liposuction or dieting tips but rather therapy and nutrition support. By this logic, immediate affirmation of a gender-crossed identity could be seen as colluding with a delusion. As one patient advocate put it bluntly during England’s recent review of youth gender services: “People with mental health conditions need robust mental healthcare. Affirming delusions is not good care. Anorexia is not affirmed, it is treated. Gender disorders are just another type of mental health issue manifested on the physical body.” () (). This perspective holds that a therapist’s job is not to simply validate whatever a client says, but to help them discover the truth about themselves and learn to cope with reality. If the reality is that a 13-year-old female cannot truly become male, a reality-focused therapy might help her come to accept her body or explore why she hates being female (maybe due to trauma or internalized sexism) – rather than immediately putting her on a path to medical transition.

This debate often centers around minors, because with adults there’s at least a presumption of stable identity and autonomy (though even in adults, therapists may encounter those who later regret being affirmed too readily). With children and adolescents, the ethical stakes are higher. Affirmation approach says that if a 10-year-old insists he is a girl, you affirm and perhaps facilitate a social transition (new name, pronouns, presenting as female) and when puberty arrives, consider puberty blockers to prevent the distress of developing the “wrong” sex traits. A more cautious approach notes that children’s identities are fluid and developing, and early social transition can cement a transient idea into a persistent one. As Dr. Soh highlighted, most young kids will revert to identifying with their birth sex by puberty – if they are not reinforced in the opposite identity (CNE.news). Thus, prematurely affirming can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The ethical question becomes: is it more harmful to potentially reinforce a false self-concept, or to withhold immediate affirmation and risk the child feeling unsupported? Reasonable practitioners can disagree, which is why some clinics favor a middle-ground “watchful waiting” (neither affirming nor actively discouraging, but monitoring the child’s development). Unfortunately, in some jurisdictions, even neutrality is frowned upon – conversion therapy bans have been written so broadly that any therapy not explicitly affirming a child’s trans identity could be interpreted as an illicit attempt to “change” their identity. Shrier warned that proposals like the U.S. Equality Act would make it “impossible for a therapist or psychiatrist to do anything other than immediately affirm a patient’s stated diagnosis of gender dysphoria — no matter the patient’s age or context”, effectively mandating affirmation only by law () (). This raises alarms about therapists’ professional judgment being overridden and about young patients being funneled toward transition without thorough evaluation.

Comparisons to Schizophrenia or Body Dysmorphia

To further illustrate the ethical divide, many have drawn analogies between gender dysphoria and conditions like schizophrenia or body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) in terms of therapeutic approach. In schizophrenia, if a patient is experiencing hallucinations or delusions (say, they believe the TV is sending them secret messages), the standard care is antipsychotic medication and therapy to help reality-testing – not to install special antennas in their house to confirm their belief. Affirmation therapy for gender dysphoria can look (to skeptics) like telling a schizophrenic patient “Yes, the voices are real and you should do what they say.” With body dysmorphic disorder, patients obsessively believe a part of their body is grossly flawed (even though it appears normal to others) – for instance, someone might be convinced their nose is hideously deformed. While cosmetic surgery is occasionally sought by BDD patients, ethical surgeons typically proceed with great caution, knowing the issue is psychological and surgery rarely solves it. In fact, BDD patients often remain unhappy post-surgery or shift focus to another body part. The parallel caution in gender dysphoria is that changing the body might not resolve the psychological distress if that distress stems from broader issues. Indeed, post-transition outcome studies show that while many trans people feel better in certain respects, rates of depression and suicide attempts can remain high, suggesting unresolved mental health needs (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender).

Those who favor affirmation bristle at the comparison to mental illness or delusion – they argue that being transgender is not a psychosis; trans people do not lose touch with reality in other domains, and their conviction of identity is not a hallucination but a deeply felt knowledge of self. They often liken gender identity to something like sexual orientation or left-handedness – an innate trait that might be rare or not obvious at birth but is fundamental to the person. Thus, they claim, affirming a trans identity is not like indulging a delusion; it’s like recognizing a truth about the person that isn’t immediately visible. Critics respond that while gender dysphoria is very real suffering (and no one is saying people “choose” it on a whim), the content of the belief (“I am a man in a woman’s body”) could be a misinterpretation of one’s feelings rather than an accurate, immutable fact. For example, a girl who hates puberty and feels uncomfortable as a female might latch onto the idea “I’m really male” as an explanation, but that could be a cognitive distortion influenced by online ideology. If that’s the case, then fully affirming that belief – analogous to affirming an anorexic’s warped self-image – might not ultimately serve the patient’s health.

There is also the analogy of somatic symptom disorders: if a patient with no leg injury insists their leg is in horrible pain and demands an amputation, do we amputate? Generally no; we treat the mind. Yet in gender medicine, perfectly healthy breasts or genitals are sometimes removed because the patient’s mind cannot tolerate them. To some clinicians, this is a necessary trade-off to alleviate extreme dysphoria; to others, it’s a profound ethical violation to mutilate healthy organs without addressing why the patient feels that way. The UK’s interim Cass Review has emphasized that many gender-distressed youth have complex psychosocial issues that need attention, and that a single-minded focus on gender transition may neglect those needs. Echoing this, a Swedish psychiatrist, Dr. Sven Román, quipped that affirming every young person’s self-diagnosis is akin to a psychiatrist affirming a depressed patient’s plan to commit suicide – obviously not something we do, because the patient’s current feelings might be tragically mistaken.

In summary, the ethical tension is between validation and verification: validating a patient’s self-professed identity versus verifying through therapy what underlying reality that identity represents. As one set of consultation comments in the NHS review put it: “The NHS cannot collude in telling lies to children about the fundamental reality of their sex.” () ()From this perspective, telling a natal male child who believes he’s a girl that he really is a girl is seen as a lie that could do harm. Others believe it is a therapeutic truth that honors the child’s inner experience. This dilemma has no easy answer, which is why it remains at the forefront of ethical discussions in gender therapy.

Medical Interventions and Minors: Puberty Blockers, Hormones, Surgeries

Perhaps the most urgent ethical questions surround the use of medical interventions in minors: puberty-blocking drugs, cross-sex hormones (estrogen/testosterone), and surgeries such as mastectomies (top surgery) or gonadectomy. These interventions are life-altering and often irreversible, raising concerns about consent and long-term welfare. An affirmation-only approach tends to favor offering such treatments to youth deemed persistent in their trans identity, while a cautious approach urges delaying or avoiding irreversible steps until adulthood. What does the evidence say, and what are the ethical implications?

Puberty blockers (GnRH analogues like Lupron) are often described by advocates as a harmless “pause button” to give young teens “time to explore gender” without the distress of developing unwanted sex characteristics. However, emerging data and clinical experience have complicated this rosy picture. For one, these blockers are not entirely reversible or benign. They halt the physical maturation of bones, brain, and sex organs during a critical window. Short-term, known side effects include loss of bone density, hot flashes, fatigue, mood changes (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia) (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia). Long-term effects on brain development, fertility, and sexual function are largely unknown (since this off-label use is relatively new and experimental in gender dysphoria) (Gender dysphoria – Wikipedia). What is known is that virtually all children put on blockers proceed to cross-sex hormones – in one study, 98% did so, meaning blockers are not really a “pause” for most but the first step of a transition pathway (). Why do almost all continue? Possibly because halting puberty at its earliest stage arrests any further development of identity and body – the young teen remains with a prepubescent body while their peers mature, which can cement the feeling of being “different” and left behind unless they proceed to live as the other sex. Shrier argues that “puberty blockers seem to nearly guarantee a child will proceed to cross-sex hormones, perhaps because of the psychological impact of having had one’s puberty blocked and being entirely out of step with one’s peers.” () In essence, blockers may create the very persistence they are meant to neutrally evaluate. Ethically, giving a 12-year-old a drug that will likely put them on a path to sterilization (since years of subsequent cross-sex hormones will render them infertile) is a grave decision. In girls, blockers plus testosterone can lead to vaginal atrophy and anorgasmia (if they later have genital surgery as adults, sexual function might never fully develop if puberty was blocked). In boys, blockers stop sperm development (no bankable sperm if given early) and cross-sex estrogen can cause irreversible breast growth and infertility. These are adult decisions being made by minors who cannot possibly understand the lifelong consequences – a point raised by the UK’s High Court in the landmark Bell v Tavistock case, which initially ruled that under-16s likely cannot give informed consent to blockers (that ruling was later appealed, but it prompted stricter oversight) (Hormonal Tx of Youth With Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden ).

Given these concerns, several European countries have recently shifted to more conservative stances for minors. Sweden’s renowned Karolinska Hospital announced in May 2021 that it would stop prescribing puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors outside of research settings (Hormonal Tx of Youth With Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden ) (Hormonal Tx of Youth With Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden ). Their new policy permits such treatments only in controlled clinical trials, citing the lack of evidence of long-term benefit and the known risks (Hormonal Tx of Youth With Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden ). The policy explicitly referenced the UK’s Keira Bell judgment and the need for caution. Finland’s health authority in 2020 also prioritized psychotherapy over early medical interventions for youth, noting that gender dysphoria in teens is often transient or associated with other issues (like autism or trauma) and that hormones should be a last resort. France’s National Academy of Medicine in 2022 warned of over-diagnosis in youth and urged great caution, recommending psychological support and parental involvement, as well as acknowledging potential side effects like sterility and bone loss from treatments (The real story on Europe’s transgender debate – POLITICO) (The real story on Europe’s transgender debate – POLITICO). These moves reflect a more classic medical-ethics stance: when in doubt, err on the side of “do no harm” and recognize that irreversible interventions require solid evidence, which is currently lacking for pediatric transition.

In contrast, in some places (including parts of the US, Canada, and Australia), affirmative care for minors remains the standard, with even double mastectomies (removal of breasts) being performed on teenagers as young as 13 or 14 in certain private clinics. Defenders of youth transition argue that for carefully selected adolescents, these interventions alleviate suffering and reduce suicide risk. However, the empirical support for the oft-repeated claim that “gender-affirming care prevents suicide” is not as strong as many believe – the studies are usually short-term and without controls, and some population-level analyses actually show higher suicide rates post-transition in youth (perhaps because underlying issues weren’t resolved). Ethically, even if there is a suicide risk, some have likened the situation to blackmail: “approve this radical treatment or the kid will kill themselves.” Normally, serious suicidal ideation would prompt intensive therapy and perhaps medication, not immediate life-altering surgery. The ethical principle of informed consent is also front and center. Can a 15-year-old truly understand what it means to be sterile at 25, or to lose sexual function? Many detransitioners (people who later revert to identifying as their birth sex) say they absolutely did not grasp what they were agreeing to in their youth – they trusted doctors who told them it was the only path forward. This raises questions of whether parents and clinicians, swept up in a one-size-fits-all affirmative model, are failing their duty of care by not fully exploring alternatives and long-term outcomes.

Finally, the role of parents and the law becomes an ethical facet. In some jurisdictions, parental consent can be bypassed for teens seeking hormones; in others, parents are pressured to affirm or risk being seen as abusive. The balance between a minor’s autonomy and parents’ responsibility is tricky. A 16-year-old may be mature in some ways but neuroscientifically, their executive function and foresight are not fully developed. We generally restrict minors from making irrevocable decisions (they can’t get tattoos, sign contracts, or drink alcohol), yet some can consent to removing their breasts or affecting future fertility. Critics call this double standard hypocritical and driven by politics rather than consistent ethics.

In sum, when it comes to minors, the ethical landscape is tilting (at least in more evidence-based systems) toward greater caution. The debate over affirmative vs exploratory therapy is not just academic when irreversible drugs and surgeries are on the table. More clinicians are asking, as Finland did, “what’s the rush?” when perhaps addressing co-occurring issues first could resolve dysphoria without drastic measures. The counterpoint is the genuine anguish of a gender-dysphoric youth; no ethical physician wants to prolong suffering needlessly. The challenge is that our interventions are high-stakes and our predictions of who will benefit in the long run are still uncertain. As one pediatric endocrinologist put it, “We need to figure out how to help young people feel comfortable in their own skin – whether that means transitioning or not – without letting ideology or fear dictate our decisions.” This encapsulates the ethical imperative: prioritize the well-being and reality of the patient over any political or social agenda.

4. Philosophical and Social Implications

Identity Beliefs vs. Medical Reality

At a philosophical level, the transgender phenomenon forces society to grapple with the nature of identity and reality. We are being asked: If someone sincerely believes they are something that their biology contradicts, should that belief be treated as a medical condition warranting physical intervention? This is virtually unprecedented in medicine. Typically, if one’s internal self-image clashes with physical reality, medicine works on the mind, not the body (as discussed with BDD or psychiatric delusions). Treating gender identity beliefs as sacrosanct – to the point of remaking bodies to align with them – raises the risk of committing category errors and harming patients who might have been helped in less invasive ways. The irreversibility of many gender medical interventions adds weight to this concern. If the identity was mistaken or transient, the individual faces lifelong consequences. Detransitioned persons often describe the devastation of realizing their identity-based medical decisions cannot be undone – lost fertility, altered voices, chest or genital scars, etc. Some have likened pediatric transition to a form of “gender eugenics” or experimental surgery on minors, given that a significant number might have outgrown their dysphoria. The philosophical question is how we define “health.” Is health the congruence of mind and body? If so, we have two paths: change the mind (traditional therapy) or change the body (gender medicine). Modern ideology has favored changing the body. But this assumes the mind’s perception (gender identity) is infallible and innate, which is philosophically dubious and scientifically unproven.

Critics warn of a slippery slope: if subjective identity claims must be accepted as reality, where do we draw the line? There are already fringe cases of people identifying as trans-species (“otherkin”), trans-racial, or trans-abled (wanting to be disabled). Society currently views those claims with skepticism, but the logic of self-identification could extend to them. For instance, if one can be “born in the wrong body” regarding sex, could someone be born in the wrong species? Such scenarios sound far-fetched, but philosophically they probe the consistency of the self-ID principle. The risk is that by medicalizing identity, we may be validating personal subjective truths that have no basis in material reality, potentially to the detriment of individuals. As one clinician starkly put it, “We need to acknowledge nobody is actually ‘transgender’; the entire premise is a lie. Let’s celebrate diversity in gender expression while keeping [healthcare] firmly planted in the reality of the sex binary.” (). This view holds that it’s perfectly fine for a man to feel more comfortable in feminine roles or attire (and vice versa), but it doesn’t make him literally female – and trying to medically make him female is chasing an illusion, since at the chromosomal and reproductive level he will remain male. You can alter secondary sex characteristics, but you cannot truly change every cell of someone’s sex. Thus, treating the belief of being the opposite sex as a condition requiring surgery/hormones could be seen as endorsing a fundamental untruth. The counterargument from trans advocates is that sex isn’t as binary as we think (they often point to intersex conditions) and that brain/mind is what ultimately matters for sex identity. Yet, philosophically, that veers into a quasi-dualism – the notion of a gendered “soul” or brain that can be born into the wrong body, which is more a metaphysical claim than a scientific one.

The Therapist’s Role: Affirmation vs. Challenging Delusion

Therapists and medical professionals are in a unique position of trust – they are supposed to help patients navigate reality, not reinforce harmful misconceptions. The role of therapists in the gender identity context has become a contentious ethical minefield. Should a therapist act more like a “mirror,” reflecting back and affirming the patient’s self-declared identity? Or more like a “compass,” helping the patient find a true direction (which might mean gently saying, “perhaps you are not actually what you think you are”)? Traditional psychotherapy training emphasizes techniques like reality testing, cognitive restructuring of false beliefs, and addressing underlying trauma or conflicts. However, many therapists now feel those standard tools are off-limits if a client says “Actually, I’m [of the opposite sex].” They worry that even asking “why do you feel that way?” could be seen as transphobic. Some have compared this to a scenario where a therapist would be expected to agree with a patient’s hallucinations – clearly anathema to their professional ethics. As a result, there is a real concern that therapists are being forced into an affirmation-only corner, effectively abandoning their duty to fully assess and treat.

The affirmation model casts the therapist almost as a cheerleader for the patient’s stated identity, helping them overcome external barriers (unsupportive family, access to hormones, etc.), rather than probing the internal consistency of that identity. But if the identity is a manifestation of something like dissociation or a misguided coping mechanism, the therapist might be abdicating their responsibility. There have been cases (shared by detransitioners) where young patients presented with a laundry list of mental health issues – depression, anxiety, past abuse, eating disorder – yet the therapist zeroed in on gender and quickly affirmed them as transgender, sidelining all other issues. From a “reality-based” perspective, this is backwards: one should treat the other issues first and see if the gender dysphoria persists once those are resolved.

Another angle is the concept of “do no harm.” Therapists must weigh harms: the harm of possibly reinforcing a delusion vs. the harm of denying someone’s professed identity. The middle ground approach for therapists has been to practice “open exploration.” This means creating a safe space for the client to explore their feelings about gender without immediately labeling them or pushing in either direction. For example, if a teen girl says “I think I’m really a boy,” an exploration-oriented therapist might respond, “Okay, let’s talk about that. When did you start feeling this? What does being a boy mean to you? How do you expect things would change if you lived as a boy?” and so on – gently guiding the patient to dig into the reasons and expectations. In an affirmative-only framework, by contrast, many of those questions might be skipped in favor of “coming out” support and a referral to an endocrinologist for puberty blockers. The ethical stance of exploration is that it’s not denying the person’s identity; it’s ensuring the identity is fully understood and not a symptom of something else. If, after thorough therapy, the individual remains convinced and shows consistency, then medical transition might be pursued with more confidence. If not, the therapist might have helped them avoid a serious mistake. Unfortunately, a number of therapists report that even this nuanced approach is often branded as “trans conversion therapy” by activists if it doesn’t affirm from the first session. This has a chilling effect, leading some to practice in secret or refer out cases they feel they can’t ethically just affirm.

Ultimately, the therapist’s role should be to help the patient achieve a healthy reconciliation of mind and body – whether that means changing the body or changing the mind. The ideological climate, however, has put pressure such that only one of those outcomes is considered acceptable (changing the body). The philosophical question is: are we helping patients by going along with potentially delusional beliefs? Or are we harming them by not challenging those beliefs? The answer likely varies by individual case, which is why a one-size-fits-all mandate (affirmation only) is so controversial. A parallel often cited: If a patient insisted on cosmetic surgery that the doctor felt was unwarranted given the patient’s appearance, a responsible doctor might refuse, recognizing body dysmorphia. Should gender-related requests be treated any differently? Many therapists and doctors feel ethical discomfort acquiescing to every demand for hormones or surgery, especially in young patients, but fear professional censure if they hesitate. Restoring a climate where clinicians can exercise judicious skepticism and treat the whole person (and all potential issues) is, some argue, essential for truly ethical practice.

Broader Societal and Legal Ramifications

The implications of treating gender identity as legally and medically enforceable reality extend far beyond individual patients – they ripple through law, education, sports, women’s rights, and societal norms. When identity claims are elevated to protected characteristics that override biological sex, society faces collisions between the rights or safety of different groups. For instance, if a transgender woman (biological male) is legally recognized as a woman in all contexts, this means male-bodied individuals in female spaces – from prisons and shelters to locker rooms and sports teams. We have already seen cases where this policy raised alarm: e.g., in the UK, a trans-identifying male prisoner (who had not had surgery) was housed in a women’s prison and went on to sexually assault female inmates. Data from the UK Ministry of Justice revealed that a plurality of trans prisoners (male-to-female) are incarcerated for sexual offenses at a much higher rate than female prisoners (Transgender women criminality shows male pattern). Critics argue that self-declared identity should not grant access to spaces where physical sex matters for privacy and safety. Similar debates rage in sports: if gender identity alone determines competition category, female athletes may be placed at a gross disadvantage against trans women who retain male physiological advantages (greater lung capacity, muscle mass, bone density, etc.). Many see this as an erosion of Title IX protections and women’s hard-won opportunities, essentially undermining the very category of “female” as a meaningful class. Philosophically, it pits the individual’s asserted identity against collective realities (like the need for fair competition or safe refuge). Society must decide if validating one person’s feelings is worth potential harm to others.

Another societal impact is on language and truth. Laws in some jurisdictions compel the use of preferred pronouns, essentially mandating others to speak as if a person is the sex they claim. For those who believe sex is an immutable reality, being forced to say “she” for a clear biological male (or vice versa) is experienced as a coerced lie – a violation of free conscience and speech. In Canada, for example, misuse of pronouns can be actionable under human rights codes in employment or service contexts. This has raised First Amendment concerns in the US and free speech concerns elsewhere. Even beyond legal compulsion, social enforcement is strong: people fear ostracism or job loss if they openly acknowledge biological realities in conflict with gender identity claims (hence the rise of terms like “TERF” used to vilify those, often women, who assert that trans women are not identical to natal women). The chilling of open discussion is a real societal consequence, making it difficult to even have fact-based conversations about these issues without accusations of “hate.” This dynamic arguably hinders scientific and policy progress, since problems can’t be solved if they can’t be discussed honestly.

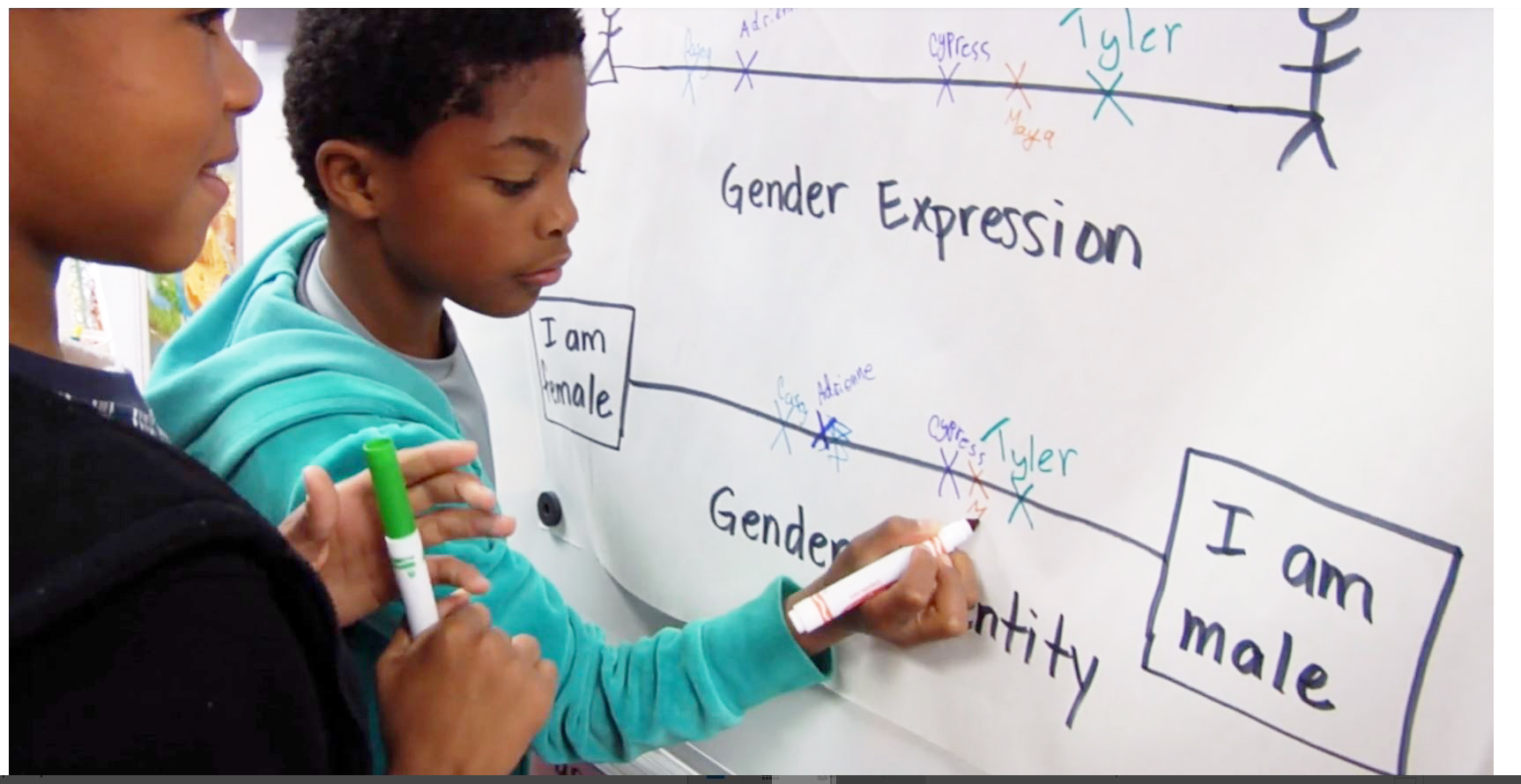

There’s also the impact on children and education. Many schools have integrated gender identity ideology into curricula, teaching very young kids that gender is fluid and you might have a boy brain in a girl body, etc. Some parents worry this confuses children about a concept (gender) they wouldn’t otherwise question, potentially sowing seeds of body discontent. Additionally, policies allowing children to change gender at school without parental knowledge (in the name of the child’s rights) drive a wedge between parent and child, raising ethical issues of parental consent and guidance. Legal recognition of self-identified gender can also clash with religious or philosophical beliefs of others. A devout religious person might respectfully disagree with the concept of changing one’s sex; yet laws might label that person discriminatory if they cannot in good conscience affirm someone’s new identity. We are thus navigating a tricky pluralism issue: how to respect transgender individuals and respect the fact that not everyone shares the same view of gender/sex.

From a philosophical vantage, treating personal identity as untouchable and legally supreme can be seen as a form of subjectivism run amok. In a pluralistic society, we generally allow people to believe what they want (“live your truth”), but we do not generally require everyone else to participate in or endorse that personal truth. With gender identity, there’s an expectation not only of tolerance (which is fair) but of compelled affirmation by others (which is more problematic). For comparison, consider religion: one may sincerely identify as a member of a certain faith, and they have the right to practice it. But they cannot force others to observe their religious dictates or to address them by religious titles if others do not share that faith. In the gender identity realm, however, the trend is that if Bob identifies as female Alice, everyone must treat Bob as female in every way – effectively forcing others to comply with Bob’s self-conception or risk being punished for “misgendering.” This elevates subjective identity to a social orthodoxy. Some feminist philosophers like Kathleen Stock have argued that this compromises intellectual honesty and material truth, effectively requiring society to participate in a “pretend” that sex is whatever one says it is, despite every cell in one’s body saying otherwise.

The legal codification of gender self-identification (for example, laws that allow changing sex markers on documents based on declaration, or defining “woman” in law to include anyone who says they are one) can also have downstream effects on data collection, crime statistics, and monitoring of discrimination. If male-bodied individuals are counted as female in, say, crime stats, it can obscure true patterns (e.g., if a male rapist is recorded as female because they identify as such, it falsely boosts “female perpetrator” statistics). It also makes targeted initiatives (like women’s health programs or scholarships for female students in STEM) harder to manage if eligibility can be attained by identity claim.

On the positive side, supporters say that legally recognizing trans identities is simply extending rights and dignity to a marginalized group, akin to how gay rights or racial equality needed laws for protection. The societal impact they seek is the normalization of transgender individuals in public life, free from harassment and discrimination. Those are noble aims. The challenge is ensuring those protections don’t infringe on others’ rights or on empirical reality. As society works through these conflicts, it will likely require nuanced policies – for instance, maybe developing solutions like third spaces or case-by-case accommodations rather than blanket self-ID in all contexts. But at present, the debate is polarized between an “all or nothing” approach: either fully validate and enforce gender self-ID or deny trans people recognition. The real world is more complicated, and a balance must be struck.

In conclusion, gender dysphoria and transgender identity sit at a crossroads of science, ethics, and philosophy. The scientific data reveals significant correlations (with autism, trauma, and mental health factors) that any comprehensive understanding must account for. The question of biology vs. ideology highlights that while there may be innate elements, the current surge in trans identification, especially among youth, has a strong ideological and social component that can’t be ignored. Ethically, the medical and therapeutic community is wrestling with how to best help individuals in distress – by affirming their identities, by exploring deeper issues, or some combination of both – all while ensuring “first, do no harm.” And societally, we are testing the limits of how far subjective identity can or should be affirmed in law and custom. In doing so, we risk blurring lines between compassion and capitulation to untruths, between supporting a minority and undermining commonsense realities. As sharp-witted commentators have noted, the truth has a way of resurfacing even when suppressed – “the truth lasts the longest,” as Debra Soh put it (CNE.news). A sustainable path forward will require acknowledging biological reality while also finding space for individuals to live free of unnecessary suffering or discrimination. That means applying both academic rigor and human empathy – not one in absence of the other. Gender dysphoria is undeniably real and painful; the challenge is to respond in a way that is clinically sound, ethically responsible, and socially sane. Only by candidly examining correlations, questioning dogmas, and prioritizing the well-being of individuals over ideology can we hope to strike that balance.

Sources:

- Warrier et al., Nature Communications (2020) – Large-scale study on autism and gender diversity ( Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity | The Transmitter: Neuroscience News and Perspectives ) (Study finds higher rates of gender diversity among autistic individuals | Autism Speaks)

- Giovanardi et al., Front. Psychology (2018) – Study on attachment, trauma, and gender dysphoria (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria) (Frontiers | Attachment Patterns and Complex Trauma in a Sample of Adults Diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria)

- Oliveira et al., BMC Psychiatry (2021) – Findings on high rates of childhood maltreatment in trans individuals ( Gender dysphoria: prejudice from childhood to adulthood, but no impact on inflammation. A cross-sectional controlled study – PMC ) ( Gender dysphoria: prejudice from childhood to adulthood, but no impact on inflammation. A cross-sectional controlled study – PMC )

- Autism Speaks summary of Nature Comm. study (2020) – Autism 24% in trans vs 5% in cis sample (Study finds higher rates of gender diversity among autistic individuals | Autism Speaks) (Study finds higher rates of gender diversity among autistic individuals | Autism Speaks)

- StatsForGender.org – Review of mental health comorbidities in gender dysphoria (various studies summarized) (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender) (Comorbidity – Stats For Gender)

- Debra Soh interview, CNE News (2022) – Critique of gender ideology in academia and mention of desistance in children (CNE.news) (CNE.news)

- Abigail Shrier, Senate Q&A (2021) – On rapid-onset dysphoria and social contagion among teen girls () ()

- NHS England Consultation Report (2023) – Public and expert comments on gender services (quotes on not “telling lies” to children and not affirming delusions) () ()

- Medscape Medical News (Nainggolan, 2021) – Sweden’s Karolinska Hospital ends routine youth hormone treatments, citing lack of evidence and U.K. court case (Hormonal Tx of Youth With Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden ) (Hormonal Tx of Youth With Gender Dysphoria Stops in Sweden )

- France24 / AFP News (2022) – French National Academy of Medicine warning on over-diagnosis, need for caution with youth treatments (bone fragility, fertility risks) (The real story on Europe’s transgender debate – POLITICO)

Beyond schools, workplaces and media have adopted new norms: pronoun declarations, gender-neutral facilities, and style guides that favor gender identity over sex (e.g. saying “pregnant people” instead of women, to include trans men). While these changes aim to include trans and nonbinary people, they have sparked debate about free expression and truthfulness in description. Some lesbian and gay commentators feel that institutions are now more focused on gender inclusivity training than on combating homophobia. For example, a company may celebrate “International Pronouns Day” but pay less attention to ongoing discrimination faced by LGB employees. This institutional emphasis on gender can inadvertently sideline same-sex attraction issues – a subtle but notable shift in diversity and inclusion programs.

Beyond schools, workplaces and media have adopted new norms: pronoun declarations, gender-neutral facilities, and style guides that favor gender identity over sex (e.g. saying “pregnant people” instead of women, to include trans men). While these changes aim to include trans and nonbinary people, they have sparked debate about free expression and truthfulness in description. Some lesbian and gay commentators feel that institutions are now more focused on gender inclusivity training than on combating homophobia. For example, a company may celebrate “International Pronouns Day” but pay less attention to ongoing discrimination faced by LGB employees. This institutional emphasis on gender can inadvertently sideline same-sex attraction issues – a subtle but notable shift in diversity and inclusion programs. Still, the very appearance of such articles shows that the impact on gay and lesbian individuals is becoming part of the public conversation. In social media, battles rage between trans rights advocates and “gender-critical” feminists or gay activists. Governments and tech companies have sometimes policed speech on these matters (e.g. Twitter briefly suspending accounts for statements like “only females are women”), framing it as anti-hate enforcement. The sociopolitical trend, therefore, has been a rapid institutional embrace of gender identity frameworks, followed by a period of public debate and reevaluation as the real-world impacts become apparent.

Still, the very appearance of such articles shows that the impact on gay and lesbian individuals is becoming part of the public conversation. In social media, battles rage between trans rights advocates and “gender-critical” feminists or gay activists. Governments and tech companies have sometimes policed speech on these matters (e.g. Twitter briefly suspending accounts for statements like “only females are women”), framing it as anti-hate enforcement. The sociopolitical trend, therefore, has been a rapid institutional embrace of gender identity frameworks, followed by a period of public debate and reevaluation as the real-world impacts become apparent.